by Alex Fielding, @alexpfielding on Twitter

I was interviewed last week by Daisy Sindelar of Radio Free Europe on the latest twist in the Vojislav Seselj saga (the article is available here). On November 6, a majority of the Seselj Trial Chamber (Judges Antonetti and Lattanzi, with Judge Niang dissenting) issued a provisional release decision on the grounds of Seselj’s ill health from liver cancer. The Chamber initiated the provisional release propio motu for the first time in ICTY history. The legal basis for this decision is problematic on a number of levels, but I couldn’t find much in the way of analysis beyond Luka Misetic’s post (in which he recommends that the Chamber issue an oral decision soon, with written reasons to follow, under rule 98 ter to try and avoid the Slobodan Milosevic scenario where a high-profile ICTY defendant dies in custody prior to judgment).

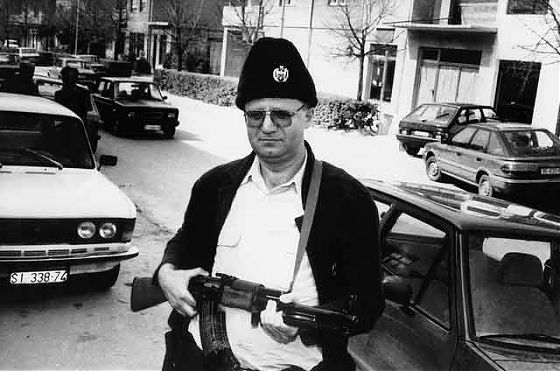

The Seselj saga has been a disaster for the ICTY, ever since he surrendered voluntarily in 2003 for war crimes and crimes against humanity charges for atrocities carried out in an effort to expel non-Serbs from parts of Croatia and Bosnia between August 1991 and September 1993.

In his eleven years of detention, he has been found in contempt of court three times for disclosing the identities of protected witnesses, refused court-appointed counsel by going on a hunger strike, and used his resulting right to self-representation to delay, obfuscate and insult those he faced during the drawn out proceedings. The Appeals Chamber’s decision to overturn the trial decision and allow Seselj to represent himself was particularly controversial as it appeared to be motivated at least in part by Seselj’s one month long hunger strike in protest of the trial decision.

Marko Milanovic’s post from August 2013 provides a good summary of the Seselj backstory:

“As for Seselj, the trial itself has been badly mismanaged almost from the very start. Seselj himself surrendered to the ICTY some 10 years ago, on the eve of the assassination of the first democratically elected prime minister of Serbia, Zoran Djindjic, by a cabal of secret police, mafia and war criminal types, of which Seselj probably had some advance knowledge. From the very get go he set out to ‘destroy’ the Tribunal, inter alia by representing himself and being disruptive to the absolute maximum. When the Trial Chamber originally assigned to his case decided to appoint counsel and deny him self-representation, Seselj went on a hunger strike. Fearing the potential fallout from Seselj dying in custody after the death of Milosevic, the Appeals Chamber made an essentially political decision to reverse the appointment of counsel and change the Trial Chamber that would hear the case, adopting an absolutist position on self-representation that is certainly not warranted by human rights considerations (note that had Seselj been tried in Serbia itself, he would have to have been represented by counsel, as is the case in many other European jurisdictions in serious cases).”

Then on 29 August 2013, as the much-maligned and delayed proceedings had finally been completed and the judges were ready to deliberate, Judge Harhoff was (rightly) disqualified for bias (see my earlier BTH posts here and here on that decision) after sending an ill-advised letter to 56 of his associates saying that President of the ICTY and Appeals Judge Meron succumbed to political pressure from the US and Israel and improperly influenced his fellow judges in the acquittals of Gotovina and Perisic.

Judge Mandiaye Niang was appointed to replace Judge Harhoff in December 2013, and was given six months to ‘familiarise’ himself with the Court record. Whether Judge Niang could adequately determine Seselj’s guilt without having heard or cross-examined any testimony directly is an issue for another post. But in any event, Judge Niang was unable to review the record one year after his appointment, and could only promise that he would be ready by June 2015. This would likely mean a judgment being rendered in late 2015 following deliberations, more than 12 years after being transferred to the ICTY Detention Unit.

Faced with the nightmarish prospect of Seselj dying of liver cancer prior to that judgment, the Majority issued its provisional release decision propio motu, which is problematic on many levels.

- Seselj still hasn’t agreed to the Chamber’s conditions and Serbia still hasn’t fully guaranteed them

In June 2014, the Chamber held a status conference with a view to provisionally release Seselj propio motu. These proceedings were suspended due to the fact that Serbia would only guarantee the Chamber’s conditions as to the security of witnesses and integrity of proceedings if Seselj agreed to them first, which he refused to do.

Since then, no status conference has been held, Serbia’s position does not appear to have changed, and Seselj still hasn’t agreed to the Chamber’s conditions of release.

Judge Niang dissents on precisely this issue – Serbia only agreed to guarantee the Chamber’s conditions if Seselj agreed to them first:

“As it had done previously, Serbia agreed to receive the Accused and to implement all the restrictive measures that the Chamber would order for him. Serbia nevertheless asked that the Accused formally confirm that he will respect these conditions.”

Rasim Ljajić, a cabinet minister who also heads Serbia’s National Council for Cooperation with the ICTY went as far as to say that the Chamber’s decision had already been made even before Judge Antonetti’s consultations with Serbia:

“The moment we received the letter of Presiding Judge Jean Claude Antonetti that asked the government of Serbia to declare itself, to all intents and purposes in two to three hours, about the conditions and about providing guarantees for Šešelj’s provisional release, it was clear that the decision was already made, considering this was the first time that such a short deadline was given to provide guarantees … This decision was above all motivated by the Tribunal’s intention to extract itself from a situation of its own making, brought on by the inappropriately long trial in the process against Šešelj.”

Serbia has now publicly stated that it would guarantee the “security of witnesses and integrity of proceedings”, however, as Judge Niang’s dissent notes, in its consultations with the Chamber, Serbia was only willing to provide such guarantees if Seselj consented to them first.

What has changed, is that the Chamber became aware of Seselj’s deteriorating health and the risk that he could succumb to liver cancer while awaiting his verdict, something it was clearly trying to avoid at all costs.

ICTY spokesperson Magdalena Spalinska has explained that the Chamber “[had] not found it necessary to consult the accused on whether he will accept these conditions as the judges deemed there was no reason to believe he would not respect such conditions.”

This logic makes little sense. Seselj has steadfastly refused to abide by the Chamber’s conditions in the past (resulting in three contempt convictions as well as a suspension of provisional release proceedings last June) and has shown absolutely no signs of changing his view. So the Chamber is pretending that he will return voluntarily and abide by its decision, while Seselj is claiming claimed victory over the ICTY in large rallies in Belgrade, vowing that he will never return to The Hague, even if a guilty verdict is rendered. All signs lead to the conclusion that the Chamber made a decision to release Seselj on very shaky legal footing, without clear guarantees that its conditions will be respected by Seselj and enforced by Serbia.

- The Chamber granted Seslj’s provisional release in the absence of his medical records or submissions from the parties

Typically, the Chamber asks for oral or written submissions in favour or against provisional release prior to its decision. This is where the Prosecution raises the threat of witness intimidation, risk of flight, etc., the defence attempts to counter those arguments, and the Chamber has the defendant and receiving State agree to a set of conditions. However, the Chamber did not seek or rely on submissions from either party. According to Daisy Sindelar of Radio Free Europe, Serge Brammertz, the ICTY’s Chief Prosecutor is quoted as saying: “it’s really up to the Trial Chamber that imposed those conditions to decide if yes or no those conditions are met. And if they consider there are violations, they can order him back to The Hague.” But how was the Chamber able to assess whether Seselj would respect its conditions as to the “security of witnesses and integrity of proceedings” (and Serbia would fully guarantee them) without a status conference or submissions for and against release?

Furthermore, Judge Niang’s dissent acknowledges that the Chamber knew that Seselj was “gravely ill … despite his refusal to allow his medical file to be disclosed officially”. The Majority decision simply states that the Chamber had “received additional confidential information that points to a deterioration in the accused’s health”. This is certainly the first case I’ve heard of where the Chamber provisionally releases the accused on health grounds without having access to, or compelling the production of, his health records. All we know is that the Chamber received some information of Seselj’s deteriorating health, but nobody knows what this information was or whether it can be appealed against.

- Where is the Prosecution’s Appeal?

According to Serge Brammertz, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) did not appeal because they had no access to Seselj’s medical records. But why did the OTP not appeal as an error of law, since Serbia did not fully guarantee the Chamber’s conditions of release? Why did the OTP not file a request to see the health-related information the Majority based its decision upon, and then appeal against that? Why did they not appeal the fact that a provisional release decision was made in absence of Seselj’s health records?

The shaky legal reasoning is certainly ripe for an appeal, particularly since Serbia’s guarantees were conditional on Seselj accepting the Chamber’s conditions, which he refused to do. The Majority refused to hold a status conference to ask Seselj to accept its conditions because it knew that Seselj would respond as he always has, by refusing to cooperate.

Considering Seselj’s contempt convictions on three prior occasions for disclosing the identity of protected witnesses, one would think the OTP would appeal a decision that could put its witnesses at risk, and make Seselj’s return to The Hague uncertain. Perhaps Brammertz wanted to distance himself from this decision and case generally, and it was convenient to use the lack of access to health records as his means to do so.

Everywhere you turn, something smells bad in this case. His case has not helped reconciliation in the region and will undoubtedly leave a black mark on the ICTY’s legacy.

“I won the battle against The Hague tribunal,” Seselj told supporters upon his return to Belgrade. “And that was my goal.” Indeed, Seselj has won many of his battles against the ICTY, and time will tell whether he wins the war.