by Peter Dixon and Maria Elena Vignoli

Are Iturians ready to speak about the past?

Photo credit: Peter Dixon

From 1999 to 2007, the Ituri district of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s northeastern Province Orientale was the scene of a deadly war that killed 60,000 and displaced over 500,000 people. In 2003, Ituri was home to at least six armed groups, with somewhere between 20,000 and 25,000 militia members. While the history is far more complex, the war was so violent in part because it pitched two of Ituri’s ethnic groups (Hema and Lendu) against each other. There’s plenty of background reading available. Dan Fahey’s 2013 Usalama Project Report is a good start.

As three out of four of the ICC’s Ituri-based trials approach their conclusion, the question looms, can Ituri be declared ‘post-conflict’? On the one hand, the November 2012 attacks in Bunia (organized and orchestrated at least in-part by the military and police), the presence of Justin Banaloki (aka “Cobra Matata”) in Walendu Bindi and Paul Sadala (aka “Morgan”) in Mambasa, and persisting land-related tensions are clear indicators that the risk of violence is still an ever-present reality for Iturians. On the other hand, reports are suggesting that a sustainable, if fragile, peace may have already emerged (also here). One thing is clear:

“There is an urgent need for a comprehensive peace process in Ituri to bridge the socio-economic and ideological gap between ethnic communities.” — Dan Fahey, Usalama Project, 2013

For the past several months, we have been interviewing leaders, stakeholders and the general population across three of Ituri’s five territories (Irumu, Djugu and Mahagi) on the issue. In total, we’ve held over 50 discussion groups and one-on-one interviews with over 170 customary leaders, civil society leaders, representatives (e.g. farmers’ representatives, youth representatives), authorities and victims’ groups. We also carried out a random survey of over 800 Iturians in Irumu and Djugu. Together with the Netherlands-based IKV Pax Christi, our goal is twofold: to better understand whether Iturians are ready to publicly speak about the acts and events of war, and if so, to identify what shape(s) this process could take. We’re still sifting through the data. In the meantime, here is some background context and some initial thoughts.

As may surprise some, the DRC already had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), established under Articles 154-160 of the 4 April 2003 Transitional Constitution. It was one of five “Institutions in Support of Democracy” laid out in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of December 2002. The CVR wrapped up its work in 2006. We spoke with several members of the CVR here in Bunia who represented Ituri on the Commission. One spoke proudly of his work there (translations from French to English here are our own).

“It was a ‘belle mission’ to investigate the events of the war and identify gross human rights violations—to establish the truth of what happened and find a way to consolidate reconciliation in Ituri.”

According to the CVR’s initial 2003 report, the Commission had grand ambitions. With a temporal jurisdiction dating back to 30 June 1960, it was tasked with (among other mandates):

- “establishing the truth of political and socioeconomic events in the DRC;

- reestablishing a climate of mutual trust between the communities and encouraging interethnic cohabitation; and

- recognizing individual and collective responsibility for crimes and violations.”

It was equally hoped that the Commission could:

- “prevent conflicts or manage them when they emerge;

- create a space for inter-Congolese expression for the consolidation of peace and national unity through truth, forgiveness, justice and reconciliation; and

- advance trauma healing and the reestablishment of mutual trust between all Congolese.”

“But we were blocked!” according to the same source.

In June 2006, the members of the CVR met in Kinshasa to reflect on the first 3 years of the Commission’s work and to evaluate its impact since 2003. The consensus was not positive. In their eventual report, the commission members noted that the CVR lacked the necessary political will and financial support from the government. Indeed, while the Commission had been granted extensive temporal jurisdiction, it had no actual budget. We were told several times how its members worked for between 18 and 24 months with no salary. In addition, the evaluation cited:

“the political, security and diplomatic contexts that were not favorable for the Commission to realize its objectives: above all the presence of belligerents and political leaders who are accused of gross violations of human rights. As long as both are in command of public affairs, it will be difficult to establish the truth as hoped.”

The reconciliation that exists in Ituri today was widely described to us as both superficial and weak. One of the major problems is that the Congolese government has failed to manage the distribution of land, which to this day separates large swathes of the Hema and Lendu communities.

Land in Ituri: still a major source of conflict

Photo credit: Peter Dixon

In our interviews, a common refrain was that people are mixed at the level of markets, churches and schools, but not at the level of land, and that there is still a lot of mistrust between the different communities. That said, our survey results from the general population seem to be showing, as others have similarly shown, that there is a strong desire among Iturians for some sort of truth and reconciliation process (It’s too early to share our exact numbers, but we can cite Vinck et al.’s 2007 data, in which 70% of Iturians said they’d be ready to publicly tell their story and almost 90% said it was important to know the truth of what happened). Most of the leaders and stakeholders we spoke to also felt that some sort of locally managed truth and reconciliation process could help consolidate Ituri’s fragile peace—not necessarily in the form of a formal Commission like that of 2003, but something to bring Iturians together to speak about and to understand their shared history.

Indeed, part of the challenge is that very few Iturians themselves actually know the history of their conflict, especially its underlying causes and the role of non-Iturians in both triggering and aggravating the violence that killed so many. This history is not taught in schools and the political economy of the war remains largely hidden at the local level, leaving rooms for rumors, lies, generalizations and suspicions to fill the void.

The scars of Ituri’s war are ever-present, but its causes remain largely hidden to the general population

Photo credit: Peter Dixon

By far the most common answer to our question, “what caused the war?” was “land conflict between the Hema (herdsman) and Lendu (farmers)”. This, however, is a gross simplification of what actually brought Ituri to war. One of the values we see in advancing truth and reconciliation here, therefore, is to complicate this story and to highlight that the land conflicts that Iturians face today were a part of the story back in 1999, but by no means the whole story. Indeed, as several leaders also pointed out to us, Iturians have been managing land conflict without such grave violence for over a century.

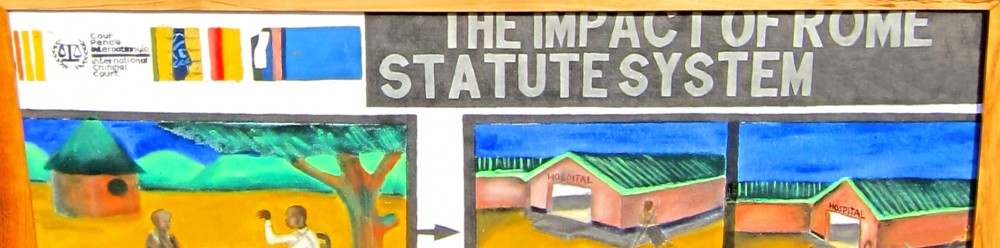

According to the great majority of leaders we spoke to, moreover, the ICC has not helped in this regard. In our discussions, we asked what role, if any, the ICC could play in promoting truth and reconciliation in Ituri, and the responses were for the most part negative. Many told us that the ICC only focused on the Hema and Lendu militias, ignoring both the other communities and the non-Iturians who were implicated. Many also said the ICC was tricked by the “faux victims” (fake victims). As such, we were told, the ICC has presented only one small part of a much bigger story. We cite these examples not because we necessarily agree, but because they were part of a common discourse we heard from all sides of the conflict. Indeed, the arrest and transfer to The Hague of Bosco Ntaganda, who represents part of the role of non-Iturians in the conflict, could very well help add some depth to this story.

In the coming months, we’ll continue to sift through our data, not only to highlight the challenges and opportunities of truth and reconciliation in Ituri, but also, hopefully, to propose some strategies about how to advance it.

Pingback: What I say may not be true, but it’s always for peace! | Beyond The Hague

Pingback: Weekend Reading | Backslash Scott Thoughts

Pingback: What does recognition mean? | Beyond The Hague

Pingback: The Ntaganda confirmation of charges decision: A victory for gender justice? | Beyond The Hague