(le français suit ci-dessous)

Welcome to BeyondTheHague.com (BTH), our blog about international justice in its many forms. We all met in The Hague working with the different international institutions and tribunals. Currently, we find ourselves involved or interested in these issues but in very different surroundings in Warsaw, Bunia, Stockholm, Malawi, Nice and Geneva. The idea behind this blog is to provide a space where we can share our thoughts and experiences around international justice in both English and French.

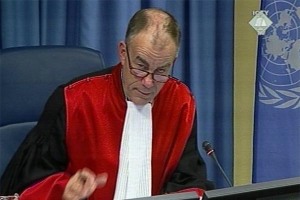

We’re starting things off with posts about Uganda’s new transitional justice policy, that letter from Judge Harhoff at the ICTY, and the controversy over the “massacre” or “genocide” at Volhynia in Poland during WWII. We’d love to hear your comments !

Please help us spread the word by linking to BeyondTheHague.com, our Facebook page, or doing whatever the kids are doing these days on Twitter (@beyondthehague). And if you want to share your own thoughts on international justice, we’ve set up a Contribute page for guest bloggers.

With our warm regards,

Alex, Manuel, Maria Elena, Marysia, Paul and Peter

—-

Bienvenue sur BeyondTheHague.com (BTH), notre blog sur la Justice internationale sous ses différentes formes. Nous nous sommes tous rencontrés à La Haye, en travaillant au sein de différentes institutions et tribunales internationales. Actuellement, nous restons impliqués ou intéressés par ces mêmes questions, mais depuis des lieux très variés : Varsovie, Bunia, Stockholm, Malawi, Nice et Genève. L’idée derrière ce blog est d’offrir un espace où nous pouvons partager nos réflexions et expériences autour de la Justice internationale en anglais et français.

Nous commençons les choses avec un article portant sur la nouvelle politique de justice transitionnelle en Ouganda, la lettre du Juge Harhoff au TPIY, et le controverse autour du “massacre” ou “génocide” à Volhynia en Pologne pendant la deuxième guerre mondiale. Nous apprécierions lire vos commentaires !

Aidez-nous à passer le mot par un lien vers BeyondTheHague.com, notre page sur Facebook, ou faîtes ce que font les ado ces jours-ci sur Twitter (@beyondthehague).

Si vous souhaitez partager vos propres idées sur la Justice internationale, nous avons mis en place une page de contribution pour blogueurs invités.

Très cordialement,

Alex, Manuel, Maria Elena, Marysia, Paul et Peter